BLOG

“There is a barbarian tribe called guitarists”

There is a movie called "My Swing". The film is about a white boy and a Roma girl named "Swing" who spend a summer at his grandmother's house in a village in rural France. The story, which begins with the boy trading his Walkman for the girl's guitar in a Roma village near his grandmother's house, is centered on manouche jazz and guitars. In exchange, the boy learns to play from an illiterate guitarist who lives in a trailer in the village and writes welfare papers on his behalf. In exchange, he learns to play from him. The boy comes and goes in the village on the pretext of learning guitar, and spends precious time with the girl in the rich nature of the river and forest.

Manouche jazz, made famous by Django Reinhardt, the "three-fingered jazzman," is a music that originated in the periphery of modern America, was distributed internationally through records and radio, and was localized in the periphery of France.

However, not only this Manouche jazz, but the series of popular music that originated in the periphery of a certain region and took root again in the periphery of a foreign country after spreading on a global scale was a glocal movement common to all genres of popular music in the twentieth century, including bossa nova, ska, and rock and roll. In this way, the guitar has always played an important role in the formation of new music and new rhythms in foreign lands.

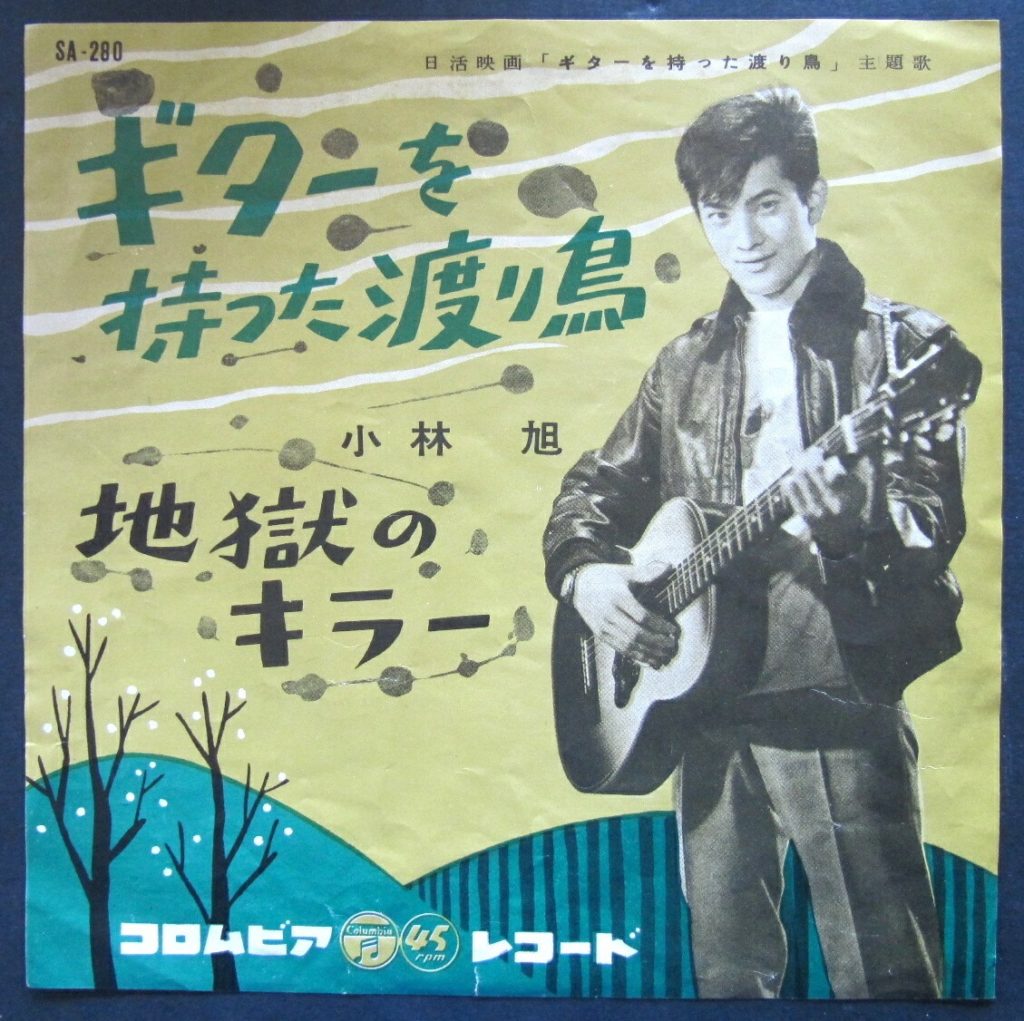

The guitar's ability to travel and perform anywhere has opened up a variety of venues and business opportunities for its musicians, and has also been a driving force in the development of new musical forms. Anecdotes such as Robert Johnson standing alone at a crossroads and selling his soul to the devil, or João Gilberto discovering the rhythm of bossa nova in the privacy of his bathroom, are the result of the mobility of the guitar. The reason why the image of the "wandering guitar player" has never left people's minds is because these guitarists had the charm of being deviants who kept escaping the shackles of place.

In contrast to a pianist who is constrained by the location of the piano, a guitarist can play whatever he wants, whether it is on the street, in a bar, or in the bathroom, as long as he has a guitar. More fundamentally, it did not even require electricity in the first place.

Guitars are also very economical (if you don't care about stuff). The guitarist can rest assured that even if one day he sells off his instrument because of his addiction to drugs or sex, he can still find a rag guitar at a very low price in any rural area. Even if the guitar is out of tune, a human being can tune it by using the pitch of his voice and the pressure on the fretboard, and it is not a big problem to play it alone. I'll use it to make some money playing on the street and in sessions, and eventually I'll buy a decent guitar again. Unlike wind instruments, if you play so quietly that only you can hear it, you won't get any complaints even if you practice in a cheap inn with thin walls. If I go to a cemetery in the middle of the night, no one will bother me… I think. Even if you are a beginner, as in the case of "My Swing," if you carry a guitar and walk down the street, you will somehow come across a kind guitar uncle who will help you without asking.

He appears out of nowhere, picks up the music of the land, and disappears at any moment. Just when you think he's gone, he comes back unnoticed, a fool from who knows where. Distant like a dream, but at the same time more intimate than anyone else, an outlaw or a recluse - the representation of such a guitarist is not unrelated to the mobility and economy of the guitar as an instrument.

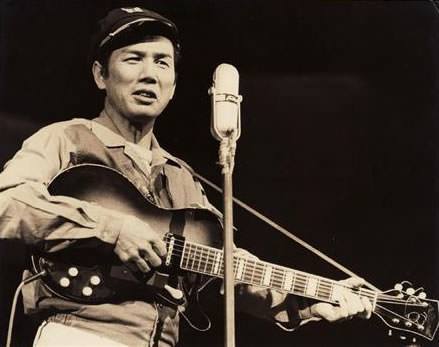

One of these "barbarians" is Yoshio Tabata, a.k.a. Batayan.

The postwar stance of the man holding a small electric guitar made by a manufacturer called "National," which no one had ever seen before, was somewhat different from that of the previous songs. He was a singer who had been popular during the war, and thus had a hand in many national policy songs, but after the war he was quicker than anyone else to see the return of Western music, which had once been "enemy music," and he was the first person in postwar Japan to play "boogie" with only a guitar and singing.

In 1947, just two years after his defeat in the war, Tabata published "Machi no Date Otoko (Zundokobushi)," which was Japan's first real down-home blues, both in poetry and style. After the war, he saw a commercial opportunity in a dub of "Zundokobusi" sung by men in black market shops that he heard on a ferry to Shikoku on a tour of the country, and he and guitarist Takaya Nagai recorded the song to sell it before anyone else. This was a year before the release of "Tokyo Boogie Woogie". Tabata reminisces as follows.

I thought this song would definitely work, so I thought of an arrangement to play it on the guitar in the boat. It was a boogie-woogie. It was before boogie-woogie was popular, but I remembered that my bandmaster at the time, a pianist named Mr. Hotta, used to play boogie-woogie in between performances. Before that, I saw a video of a black woman playing boogie-woogie on the piano, and I was amazed. Her left hand was bumbo-bumbo-bumbo-chan-chan. That's what I had in my mind. It would have been stupid to play this song like a normal song, bum cha cha, bum cha. Yeah. That's right, I thought, let's try boogie-woogie together. Yoshio Tabata*]

How would this song, sung by a wandering Tabata carrying a guitar, have resonated with the masses of Japan in the early postwar period, confused by the sudden shift from fascism to democracy and poverty? Although the lyricist is not the same person, when he sings, "Yakuza toyo mo ano musume no tame ni, saraba o saraba sayonara" (Farewell to the Yakuza, for the sake of that girl, farewell to the yakuza), it is as if he is releasing himself and the masses, who were busy cooperating in the war, from the spell of the past. Even if the words were perceived in different ways, what was the meaning of the "boogie" rhythm played on the guitar at that time and place? I would like you to recall how jazz, after its glocal indigenization, was marginalized again in a foreign land. In Tabata's case, it was the "boogie" and the "zunduko bushi" that he heard during his tour in the early postwar period.

*Yoshio Tabata, "Postwar Nippon's Popular Music," Record Collectors, June 1998. The quotation is from Masakazu Kitanaka, "How the Guitar Changed Japanese Songs: A Popular Music History of the Guitar.

UG Noodle